In 1981 my wife Katie and I spent months planning a week-long vacation in Alaska’s Glacier Bay National Park. We wanted to see Muir Glacier, one of the few “tidal” glaciers left that flow all the way to the ocean. Little did we know that we would have five days of steady freezing rain and sleepless nights fearing tsumanis and grizzly bears.

We were living in Seattle at the time. I was doing a one-year Internal Medicine internship and Katie was working as a legal assistant. We had heard about the Muir Glacier, and the spectacle of large chunks of ice falling into the sea, creating ice bergs (called “calving”). We also heard that it was retreating rapidly with global warming. We decided that this could be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that we couldn’t afford to miss.

I found a Labor Day vacation package for about $300 per person—including round‑trip airfare from Seattle to Glacier Bay and one night’s stay in the Glacier Bay Lodge. But rather than staying in the comfort of the lodge and viewing the glaciers from a tour boat like most people do, we decided to kayak up to where the Muir Glacier meets the ocean and wilderness camp for five days.

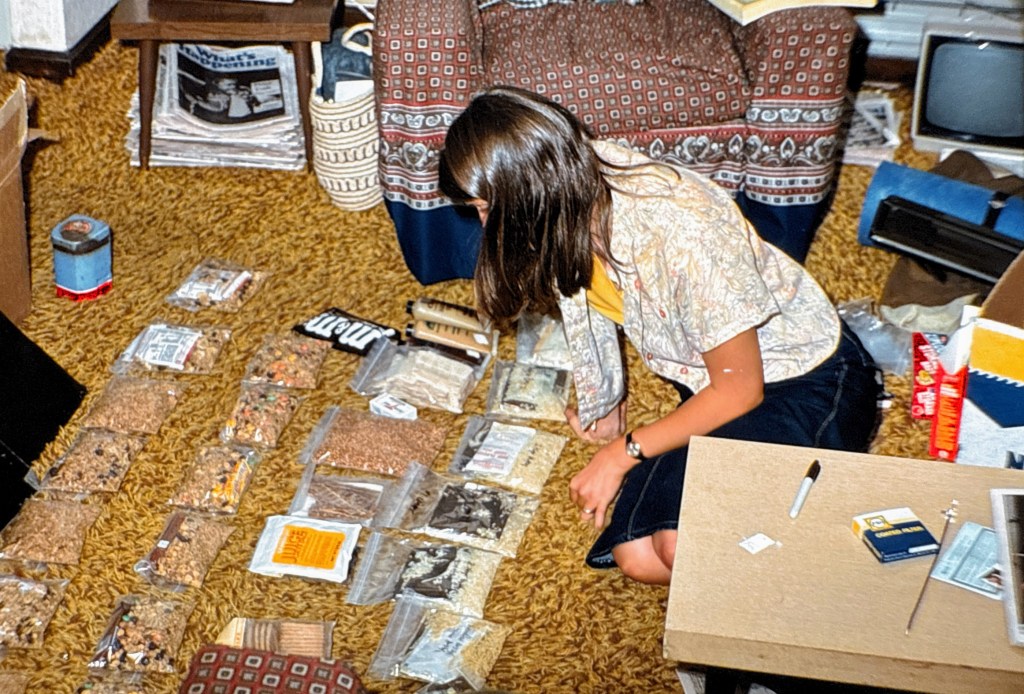

We carefully packed all our necessary clothing and food for a week, in a two-person kayak.

We arrived at the Glacier Bay National Park Visitor Center, near Gustavus, on Saturday afternoon, September 5th. We met the outfitter and went to pick up our Easy Rider two‑person kayak, rigged with spray skirts and water‑proof bags. Our plan was to pay for a shuttle on the rustic Thunder Bay tour boat to take us up the East Bay and get dropped off at the Wolf Point ranger station.

We’d kayak in further up the inlet to see the Muir Glacier, spend five nights camping, and then return to Wolf Point to meet the boat for the ride back to the Glacier Bay Lodge at 2 PM sharp five days later.

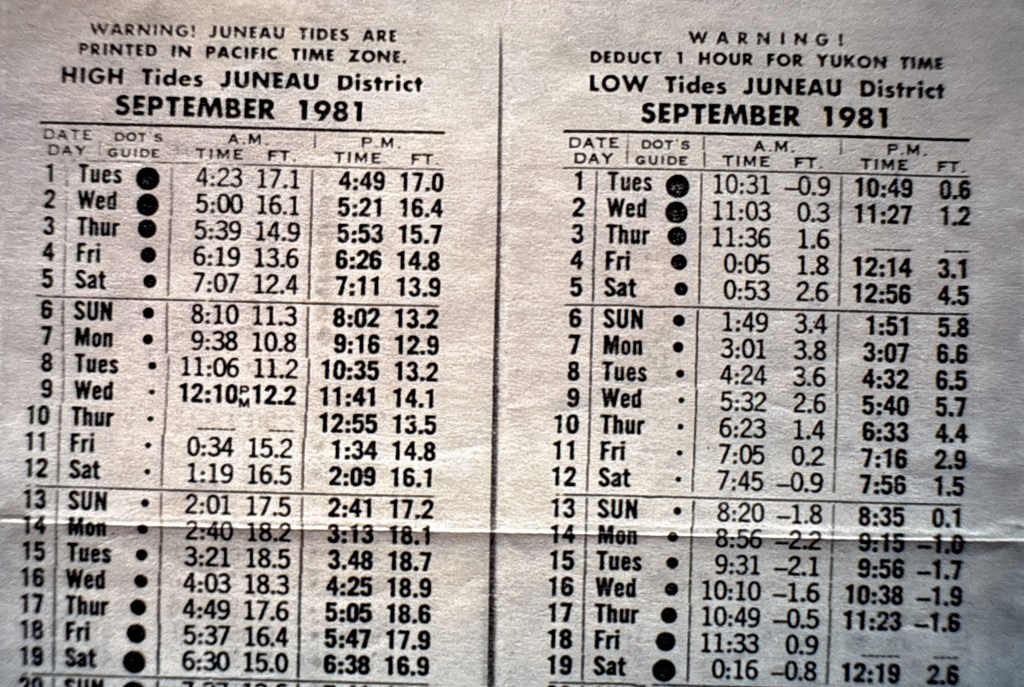

The outfitter also gave us a tidal chart and reminded us that because of the narrow inlets, Glacier Bay has tidal swings of up to 25 feet. During times of peak flow of water into and out of the bays, bottlenecked areas can create strong currents and rough water, especially at the mouths of narrow inlets. He told us that it would be safer and easier to travel during the lowest water level (called a slack tide) or in the same direction as the tidal current.

The first night, we relaxed in the lobby of the Glacier Bay Lodge and decided to splurge on our last supper before heading into the wilderness. We split a Dungeness crab meal costing $15.

The next day, we awoke early to a pounding rain. We were glad that we were warm and dry sitting in our room and not out camping in our tent. Little did we know that the nice weather the night we arrived was the exception. It was September in southeast Alaska and the winter rains had started in earnest.

We skipped breakfast and joined the others for the 7:30 AM boat departure. We were dressed head to toe in our wool and rain gear. Most people were riding up the bay to Muir Glacier and back the same day. One guy and a party of two women were camping up the bay just for the night.

We learned only then that this was the last day of the season, and that they would be hauling the floating Wolf Point Ranger Station back to the lodge the next day. I guess there weren’t many people who came up the bay to camp this time of year. Oh well, we knew that we wouldn’t have any trouble finding a campsite.

On the boat ride up the bay, the ranger pointed out to a campsite on Sandy Cove that was closed in 1980, due to grizzly bear activity. A kayaker had been killed while camping there in 1976 and again in 1980. In that attack, a 25-year-old man had been eaten by the bear. Searchers found only his bare skeleton, one intact hand, and both feet still booted (more information here). Just what we needed to hear before our first night in the tent

The rain was still pouring when we got to Wolf Point around noon. They lowered our kayak into the icy waters and we hopped in. Fortunately, the tide was at its lowest point, so the paddling was easy and we were able to stay close to shore and avoid hitting any of the icebergs.

We decided to keep paddling north, about 12 miles to the end of the Muir inlet. It was late and very cold, so we set up camp on a rocky knoll next to a rushing glacial stream on the east side of the inlet. The rain had let up so we enjoyed our first dinner keeping a distance from our tent as a bear precaution. As we finished dinner, the rain returned and forced us into our tent for an early night.

We awoke in the middle of the night to find the tent filling with water. My careful seam sealing had not included the tent fly and this omission proved to be a headache throughout the entire trip. It rained all night long.

Early the next morning, I noticed that the bank of the stream next us seemed to be getting closer to our tent. To test this hypothesis, I placed 12 rocks, one foot apart, leading from the stream to the edge of our tent. I retired to the tent to get warm. Katie was sitting in her sleeping bag dreaming of Hawaii and wondering once again why she married me.

I went out about a half an hour later and found that only nine rocks were left. At this rate, I realized that our tent would be in the water by lunchtime. But first, I wanted to find out why the water was washing away the bank of the stream so fast. So I climbed up the hill about 20 feet and saw that the water was cascading down from underneath the glacier above.

Apparently, because of the heavy rains, the streams were engorged and were eroding the rocks that had been deposited by the glacier. I jumped across a small stream to get a closer look and saw something that was truly out of this world.

Before my eyes, rocks the size of basketballs were being hurled down the stream. They rolled, flew, and crashed down the stream bed. As more rocks tumbled down, they began to pile up on each other. Two large rocks would settle down, a third would wedge between, and a fourth. Soon the rocks dammed the flow of the stream in front of my eyes. In amazement, I started to return to our tent to tell Katie.

Then I realized where all the water had gone. The water from the stream that I was observing had been forced down another branch between me and my tent. The small stream I jumped over only minutes before was now 15 feet wide and rushing down the mountain. Even as I stood there contemplating my plight, the stream widened and continued to swell. I thought about jumping and even tried to step onto a boulder to get across.

But I realized that one slip and I would be washed down with the boulders into Glacier Bay. I sat down. There was no way back to the tent. Just then, Katie appeared on the other side of the rushing stream. Although she was only a few feet away, the rushing water and thundering of the boulders drowned out our voices.

Shouting at each other, we decided that she would get into the kayak, and paddle around in the inlet to pick me up. But just then, the water in the stream seemed to stop. I looked up and could see the water rushing from above, but I decided to go for it. I jumped on two rocks and dove for the other shore. I came up short but managed to scramble up the bank before the water rushed back.

We walked back to the tent and noticed that there were only five rocks left. The rain had just let up and the wind started to blow so we took down the tent, dried our gear, and moved the tent to a safer location.

We ate lunch and went for a walk up Eldridge Mountain to get a fantastic view of the Muir Glacier.

It seemed to be so tiny from our perspective. Looking back to where our tent was, we realized how alone and isolated we were.

That night while in our tent, Katie was reading a guidebook. She read: “Although landslide-generated tsunamis are historically uncommon in Glacier Bay, there have been plenty of landslides in and near the park, and some of them have produced tsunamis…one tsunami reached 1,720 feet above sea level on the opposite shoreline and killed two people in a small boat.” She repeated to me, “Two people in a small boat? Seriously?”

For the rest of the trip, Katie would wake up during the night thinking that she heard an approaching tsunami. But realizing it was just a dream she would fall asleep, until a grizzly bear appeared in her next dream.

The next morning, we woke up to a deep red sunrise. Remembering that a “red sky at morn, sailors be warned,” we knew that the rain would be coming back. So, we packed up our tent early and paddled up close to the wall of the Muir Glacier. We spent about two hours photographing seals and watching the glacier calve chunks of ice, some large and others small, that would become icebergs. The overcast sky gave the massive wall of ice a deep blue tint.

It got cold being so close to the ice, so we paddled south back towards Riggs Glacier, and into—you guessed it—more rain. About three hours later we had camp set up on a rocky knoll overlooking Riggs Bay. The rain kept coming and coming and coming. Sitting in our tent, it continued to rain but our tent was dry, so we slept well. That night we heard what sounded like thunder, or jets flying in the distance.

It rained all night again and through the next morning. We waited for it to stop but when it didn’t, we put on our rain gear and headed out for a hike. We discovered what we thought had been jets flying overhead were actually large rocks and ice boulders rolling underneath in streams beneath the glacier. It was truly amazing.

On our return, we saw incredible ice bergs, large and small, that had been deposited on the shore during high tide. They acted as refrigerants, dropping the temperature to around freezing. And many of them looked like they had been sculpted by ocean water into the amazing shapes, resembling animals of all shapes and sizes. One looked remarkably like a snail, frozen in search of food and shelter.

After five days, we ready to return to civilization and paddle back to the rendezvous site and Wolf Point. However, as we headed out it began to rain again and the wind picked up, causing the ice bergs to bob up and down in the two to four-foot waves. We decided that it was too dangerous to paddle in these conditions and realized that we would not make it to our rendezvous site at the agreed-upon time.

So we stopped and climbed up on a large outcropping, overlooking the channel. We knew that the boat would come by shortly, taking tourists up to view Muir Glacier. On schedule it appeared, but with the rain, our shouting and waving of hands went unnoticed.

We knew that it would return in about 30 minutes, on the way back to Glacier Bay, so we prepared by getting out our flare and a freon horn (brought along to ward off grizzly bears). As the boat approached, we lit the flare and began blowing the freon horn, but the boat kept going.

Just as we thought they’d missed us, one sole passenger who was sitting at the back of the boat noticed us. He ran inside, and the boat slowed, and turned back.

After five days of near freezing temperatures and constant rain, the weather on the ride back was glorious. As the sky cleared and the sun came out, the views of the Fairweather mountain range were breathtaking.

We arrived at the Glacier Bay Lodge and wished that we could afford to stay there, but instead we set up our tent nearby. As Katie was showering at the campsite, I heard that a 324-pound halibut had been caught. I ran to see it but found instead two large chests filled with fresh filets.

A fisherman looked at me and asked, “Are you camping?” When I responded, “Yes,” he said, “You should have some fresh fish for dinner” and proceeded to give us two filets. We stuffed ourselves with fresh halibut, a bagel, plus $6 for four beers. There was enough fish left over for lunch the next day.

The weather continued to be great our last two days. We enjoyed walking in a rain forest, and along the beaches when the tide was out. We also paddled around, and saw lots of wildlife, including black bears. We realized then that during our five days near the Muir Glacier, the landscape was stark and devoid of life and colors.

Thinking back now, and with the benefit of age and experience, our kayak vacation in Glacier Bay was risky. We should have had wet or dry suits. But we’re glad that we did it and survived to tell about it.

More photos of our trip are here: https://photos.app.goo.gl/iTFCms3h5LxEAVn68

Afterword: The Muir Glacier continued its retreat after our visit. A few years later, it no longer reached the ocean and stopped calving icebergs. In 2012, the award-winning film Chasing Ice documents the urgency of climate change, showing a glacier calving event that took place at Jakobshavn Glacier in Greenland, lasting 75 minutes, the longest such event ever captured on film (more here). It turns out that our visit to see the Muir Glacier calve icebergs into the ocean, was truly the last in a lifetime.

Leave a reply to Tom Geppert Cancel reply